Total Work Newsletter #15: How to Care Less About Any Career Whatsoever

Total Work, a term coined by the philosopher Josef Pieper, is the process by which human beings are transformed into workers as work, like a total solar eclipse symbolized in the logo above, comes to obscure all other aspects of life. In these newsletters, I document, reflect upon, and seek to understand this world historical process, one that started at least as far back as 1800 and possibly as early as 1500.

Observation: You’ll notice that there are two very different voices speaking in Issues #1-15. The first is a critical voice, for it is this voice that examines matters closely and is often critical of manifestations of total work. You should be able to feel the tone of voice of criticality. The second is a lyrical, contemplative voice, one that is nearing a praise song. The idea, here, is to bless existence sub specie aeternitatis (from the viewpoint of eternity). Outside the maw of total work, Life can be very sweet. It’s waiting for us.

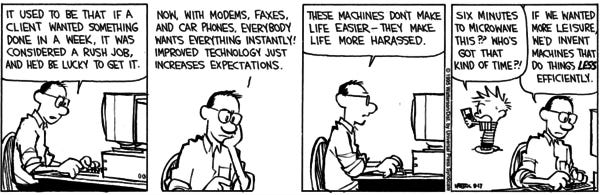

Calvin and Hobbes on the Acceleration Society

Credit: Solveig Gautadottir

This is what one sociologist, Judy Wajcman, calls the “time-pressure paradox.” How do we explain the fact that the pace of life in modern culture seems to be speeding up? My forthcoming Quartz at Work piece will discuss our “time famine.”

I Do Know How to Pay Attention

Mary Oliver, “The Summer Day” (1990):

Who made the world?

Who made the swan, and the black bear?

Who made the grasshopper?

This grasshopper, I mean–

the one who has flung herself out of the grass,

the one who is eating sugar out of my hand,

who is moving her jaws back and forth instead of up and down–

who is gazing around with her enormous and complicated eyes.

Now she lifts her pale forearms and thoroughly washes her face.

Now she snaps her wings open, and floats away.

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

A prayer, actually, just is paying attention to what exists. Lovingly. Reverently. Patiently

#1: HISTORY OF WORK | A 1,000-year Rear-view Mirror on Work | 2 min. | Axios | Newsletter

Axios Opening: “In the 17th century, Europeans worked largely from their homes, often as artisans and farmers. Each family member had a hierarchical place in the flow of tasks, attuned to their age and skills, and were acknowledged for that contribution.

My Brief Take: I don’t that I’ve already included a link in the last issue to this book, but I feel it’s important. Over the last year, I’ve yet to come across a good long history of work. I’ve ordered a copy of this book, and I’d like to see whether it fulfills such a promise.

#2: ENTREPRENEURSHIP | Why Entrepreneurs Start Companies Rather Than Join Them | 5 min. | Steve Blank Blog | Analysis HT Khe Hy

Overview: Steve Blank interprets an important paper on entrepreneurship. You suggests that there are two big takeaways: 1.) “Entrepreneurs start their own companies because existing companies don’t value the skills that don’t fit on a resume.” 2.) “The most talented people choose entrepreneurship (Lemons versus Cherries).”

My Take: First, what can be good about entrepreneurship is that it can enable you to have a livelihood while also decentering the place of work in your life (i.e., contra total work). Second, what’s left out of this account is the idea that having a job, as I argued in my latest Quartz piece, is at least a sacrifice: it involves, again at least, a sacrifice of freedom.

Mystery, Illumination, and Form

1. Religion or spirituality is concerned, for this is its ken, with ultimate mystery.

2. Contemplative art (shall we say) is concerned with creating a space in which something can come alive as well as with the formed actuality of that something coming to life.

3. The marriage of (i) religion or spirituality and (ii) contemplative art is awe or marvel (in the first instance, i.e., in that of religion or spirituality) and joyous beauty (in the second instance, i.e., in that of art).

4. If (as I recently wrote in a journal) contemplative philosophy is the illumination of an intuitive insight (where an intuitive insight would be of this form: “something has happened, something significant, and yet it cannot yet be put into words”), contemplative art is the form an intuitive insight takes. Contemplative philosophy illumines, contemplative art shapes.

5. In sum, the point, ultimately, is the direct experience of mystery. To illuminate the wordless mystery: this is the responsibility of philosophy. To give form to this mystery: this is the responsibility of contemplative art.

#3: LOAFING | Baby Boomers Reach the End of Their To-Do List | 5 min. | NYT | Opinion HT Dylan Willoughby

NYT Sum: “This isn’t sloth. It isn’t exhaustion. It’s finally being aware of existing for its own purpose.”

Quote: “Other cultures labor, but what other nation implores each citizen to tackle happiness as a solo endeavor, a crazy paradox of a hunt for something that cannot, after all, be earned but can only be bestowed from the mysterious recesses of life? Give it up. Waste the day.”

Remark: I’m not sure that I’d want to resuscitate “idleness” (Bertrand Russell) or “loafing” (Walt Whitman); I think it far wiser to come up with another term (such as leisure), one that’s not caught up in dualities (work hard/loaf around, etc.). Still, I think this author is pointing us in the right direction. As I’d put it: meaning is none other than grace.

#4: CRITIQUE OF 'THE JOB' | Does Everyone Really Need a Job? Why We Should Question Full Employment | 5 min. | Big Think | Opinion

Big Think Sum: “Does everybody really need to work? What three philosophers [Bertrand Russell, David Graeber, and Andrew Taggart] have to say about our dedication to finding everybody a job.”

Quote: “This is the question Andrew Taggart has asked for years. Taggart, a practical philosopher, understands that people have a need to contribute and often find meaning in work, but questions if our society can offer jobs that fulfill these needs to everybody. He points out that full employment schemes have historically focused on short-term, unskilled and labor-intensive employment that often fail to satisfy our need to contribute meaningfully to the world.”

Remark: Not exactly accurate. (1) I didn’t argue for “meaning in work” (since I’ve argued elsewhere that meaning is precisely what occurs beyond all human effort). (2) Also, I didn’t say that full employment schemes were of that sort but rather quoted John Elster who suggested that trying to guarantee the right to work wouldn’t be feasible except in this undesirable fashion.

There is More Beauty than Our Eyes can Bear

The minister John Ames speaking in Marilynne Robinson’s novel Gilead (2004):

I love the prairie! So often I have seen the dawn come and the light flood over the land and everything turn radiant at once, that word “good” so profoundly affirmed in my soul that I am amazed I should be allowed to witness such a thing. There may have been a more wonderful first moment “when the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy,” but for all I know to the contrary, they still do sing and shout, and they certainly might well. Here on the prairie there is nothing to distract attention from the evening and the morning, nothing on the horizon to abbreviate or to delay. Mountains would seem an impertinence from that point of view.

Careers vs. Leisure, 1800-2008

Frequency of Uses of "Career" and "Leisure" in Google Books, 1800-2008 HT Paul Millerd

How to Care Less about any Career Whatsoever

Preamble

A curious piece of evidence to begin with: a 6-week course I’m taking with 11 other people started this past Monday. The course, which is concerned with how to be clearer and which seemed to me a good occasion for trying to think more clearly about total work, is held over Zoom. All 12 are living in different parts of the world (though most, I think, are citizens of different European countries). And now for the trippy part: each of us was invited to introduce ourselves, and to a T all others talked immediately about his or her work and, because the course is about clarity, about what sorts of things related to work that he or she would like to be clearer about. I was stunned, marveling at the fact that each person thinks that he or she fundamentally is a certain kind of worker. Very uncanny.

Wait but Wait but Why

Tim Urban, in his popular blog Wait but Why, recently wrote an extraordinarily long blog entitled “How to Pick a Career (That Actually Fits You).” Although I have nothing against Urban, I see his very long post (which–confession here–I didn’t read in its entirety) as a textbook case of total work. And so, I’ve elected to share with you my critique of it.

My Approach to Reading the Post

I wanted to pay close attention to the justification Urban gave for writing such a loooooong piece. Why was it so long? This is rich territory should one want, as I do, to examine the assumptions that someone is making. Then I used Command-F to search for “career” in order to see how the term was being used.

Claims (Stated and Largely Undefended)

1.) Having a career is a pale substitute for the Death of God. They presuppose an “agent theory,” the idea that human beings are fundamentally agents, rather than older view that we are made in the “image of God” and therefore should contemplate our place in the cosmos (here see Edward Craig’s The Mind of God and the Works of Man).

2.) Notwithstanding Urban’s “millennial view” of work as a yearning-filled journey through life (hence his oft-employed metaphor: “career path,” which he occasionally, and quite tellingly, conflates with “life path”), he takes on board many of the total work assumptions, those that I’ve been seeking to challenge in this newsletter and beyond.

3.) In September 2011, it dawned on me that careers qua careers weren’t that important. I hypothesized that the “very idea of a career may be coming to an end.” There, I suggested (and this would doubtless need to be re-examined) that one could only have a career provided that all five conditions were met:

First, you had to complete the appropriate training, the result being either the relevant certificate or degree. Second, you had to work for an organization or a certain kind of organization. Third, you had to stay long enough in your selected field. Fourth, there had to be a clearly laid-out course of progress or path of advancement. Fifth, there needed to be readily identifiable pinnacles of success. A career, accordingly, was a structure of meaning, a narrative of self-development without reference to God, nation, or family.

In other words, careers themselves rest on a particular set of intelligible social institutional structures, and if those structures are in flux (as I thought they were and as I still think they are), then the career qua career may pass out of existence. Now, whether the argument that the institutional conditions that enable particular careers to be actualized are coming apart at the seams is sound is debatable. Still, the greater value of the argument is, I think, the suggestion that a career is a form of “self-development without reference to God, nation, or family”: that is to say, it is predicated on a free agent who has already severed communal or social bonds, who makes no appeal to a higher order of reality, and who must make his or her way in the world through the world of work. I believe this is a mistaken conception of a life well lived. To say, then, that the career is not that important is to say, in key part, that it cannot fulfill our spiritual longing to be in communion with higher reality and, indeed and also worse, that it may be obscuring that spiritual longing dwelling nascently within us.

4.) Careers presuppose “Protestantism,” a view I gently opposed in this Quartz at Work piece. As such, they seem to me rather fancy ways of fetishizing what is otherwise a jejune, mundane activity, dressing up “what I do” to make it look to others as if it were jazzy and cool (on a particular kind of coolness, “ethical coolness,” see last week’s issue). It seems to me reasonable, and prescient, to decouple some idea of life as a journey (or better: “life is a search to understand why we’re ultimately here”) from the further idea of that life journey being identical with a work journey. Indeed, as we’ll see at the end of this essay, life gets really opened up once we decenter work.

Main Objections to Careers

I’ll define a career perhaps too loosely as a certain kind of story one tells oneself, which story is meant to make a discernible pattern out of whatever work experiences (jobs, gigs, promotions, etc.) or work accomplishments one has had.

Objection #1: Careerism is basically a form of narcissism (HT Peter Limberg), a way of making oneself “feel special.” Without thinking, see how you feel when you read the following items: pipe fitter, carpenter, professor, CEO. (Hint: the first two aren’t careers while the third and fourth are.) This narcissism is, in addition, a socially acceptable form of tacit bragging. (“Check out my resume or CV: look at how freakin’ great I am.”)

Objection #2: Relatedly, having a good career is motivated, at least in part, by the idea that one would thereby be “impressive” in the eyes of others, especially one’s peer group (HT Khe Hy).

Objection #3: Careerism is an inadequate substitute for the Death of God. It claims to provide one with meaning, but it cannot make up for the “God-shaped hole” (Pascal) in modern culture.

We’ll discover both narcissism and the plug-in-for-meaninglessness implicit in Urban’s post, which I examine below.

Considering Urban’s Justification

Urban asks why picking a career path is so darn important. Let’s go through his reasons in reverse order. I’ll start with the later, personal reason he gave and then make my way back to the societal reasons he gave. I’ll use the underlining feature to draw the salient points to your attention.

Personal reason first:

On top of having my own story to look at [he writes], I’ve had a front-row seat for the stories of my dozen or so closest friends. My friends seem to share my career path obsessiveness, so between observing their paths and talking with them about those paths again and again along the way, I’ve broadened my views on the topic, which helps me to distinguish between the lessons that are my-life specific and those that are more universal.

This, to me, is the crux. Urban never stops to question why he and his friends are obsessed with their career paths. Why on earth would any reasonable person obsess over something as insignificant as a career? Over the years, I’ve heard something similar from a number of tech-based workers at, say, Twitter, Google, and Facebook. Given that a career is not a terribly interesting thing, what is fundamentally missing in their lives such that some people think it reasonable to obsess over a career or a career path? What pebble in their shoe (dukkha) has yet to be looked at? Death? The threat of nihilism? Egoic insignificance? Preternatural restlessness? Examine this question and the rest of the post doesn’t need to be written.

But let’s go on anyway and take a look at the societal reasons:

Time. For most of us, a career (including ancillary career time, like time spent commuting and thinking about your work) will eat up somewhere between 50,000 and 150,000 hours. At the moment, a long human life runs at about 750,000 hours. When you subtract childhood (~175,000 hours) and the portion of your adult life you’ll spend sleeping, eating, exercising, and otherwise taking care of the human pet you live in, along with errands and general life upkeep (~325,000 hours), you’re left with 250,000 “meaningful adult hours.” So a typical career will take up somewhere between 20% and 60% of your meaningful adult time—not something to be a cook about. [Total Work Thesis #1: Work is central to life. –AT]

Here is Total Work Thesis #1: work is the center around which the rest of human life turns. And, man, if I had a nickel for every time I’ve heard that comment, I’d be a wealthy man. A few examples I stumbled upon: in “Why We Can No Longer Separate Work from Life (and Shouldn’t),” Dan Schawbel starts off one sentence with a telling dependent clause: “Since we spend so much time at work…” In “The Idea of Work is Wrong,” similarly, the writer makes the same assumption: “Given that we all have to make a living and that doing so is going to demand a big chunk of our time.” What do the assumptions in these articles (and countless others) imply about the nature of the work society, the society we can’t seem to climb out of in order to think beyond it? The cultural, historical, and historical myopia runs deep. No consideration is given to the onset of the Industrial Revolution, to the working conditions during the Victorian period in England, to the labor movements in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, to the more recent pushes for four-day workweeks. Really, the self-evident idea that work shall necessarily ‘eat up’ as much as 60% of my “meaningful adult life” is not only preposterous but also starved of imagination.

Next:

Quality of Life. Your career has a major effect on all the non-career hours as well. For those of us not already wealthy through past earnings, marriage, or inheritance, a career doubles as our means of support. The particulars of your career also often play a big role in determining where you live, how flexible your life is, the kinds of things you’re able to do in your free time, and sometimes even in who you end up marrying.

Oh, Lord. Here is Total Work Thesis #2: everything else is derivative of as well as subservient to work. Must one’s work have a “major effect” on one’s “non-career hours”? Must? Also, I argue that we should decouple right livelihood from having a job or a career in my latest Quartz at Work piece.

Next:

Impact. On top of your career being the way you spend much of your time and the means of support for the rest of your time, your career triples as your primary mode of impact-making. Every human life touches thousands of other lives in thousands of different ways, and all of those lives you alter then go on to touch thousands of lives of their own. We can’t test this, but I’m pretty sure that you can select any 80-year-old alive today, go back in time 80 years, find them as an infant, throw the infant in the trash, and then come back to the present day and find a countless number of things changed. All lives make a large impact on the world and on the future—but the kind of impact you end up making is largely within your control, depending on the values you live by and the places you direct your energy. Whatever shape your career path ends up taking, the world will be altered by it.

I guess you could call this the revised social entrepreneur version of Total Work Thesis #1: work just is central because it’s what can create maximum social impact. Here, you have to assume our impoverished wage-based work society–that is, a particular Weltbild– in order to get this case off the ground. Assuming the 'veracity’ of the work society, then your career could be “your primary mode of impact-making.” But does it have it be? How about raising a child? How about your ongoing, potentially intergenerational relationship with your church? How about your care for your dying parents? What about ethics broadly understood, civic engagement, love of others, artistic expression, or spiritual practice? This whole 'impact fetish’ is getting very old.

Lastly:

Identity. In our childhoods, people ask us about our career plans by asking us what we want to be when we grow up. When we grow up, we tell people about our careers by telling them what we are. We don’t say, “I practice law”—we say, “I am a lawyer.” This is probably an unhealthy way to think about careers, but the way many societies are right now, a person’s career quadruples as the person’s primary identity. Which is kind of a big thing.

Total Work Ur-Thesis: You are basically a worker; that’s just who you are. There’s really no better way to live your life “asleep” than by assuming away one of the biggest questions you can possibly ask: who am I? If you continue to insist that who you basically are is a certain kind of worker, then you’ve essentially outsourced your life to social conditioning. And that may be one of the greatest silent tragedies: a life, one’s own, that goes unlived.

Oh, Open Me Up, Life!

Open parenthesis: in the future, I think it could be illuminating to write a bit about some of the non-ordinary (or mystical) experiences that I’ve had or that others have shared with me. (William James’s The Varieties of Religious Experience remains, to my mind, a very helpful guide.) These were not “other-worldly” or “supra-worldly” in nature; they were instead perceptions, sometimes lasting, at other times fleeting, of how the world–our world–is from the viewpoint of eternity. When you’ve had any kind of experience involving even the faintest glimpse of ultimate reality, then thoughts of work seem not entirely unimportant (for work has its minor, subsidiary place in human life) but rather far, far less so. Close parenthesis.

This critique of careerism is meant to open us up to Life, the great mystery of existence. The questions that can pierce our skins and our hearts are many, are varied, are beautiful. What is Life? What is my life about? How does my life fit into the furniture of the universe? If life were construed as a journey, what could that journey be like if work were no longer central to it? What is beauty? What grand? What marvelous? What is worthy of dying for? What is so unspeakably glorious as to cause one–genuinely and unabashedly–to weep?

On Gratitude

A Grateful Day with Brother David Steindl-Rast HT Peter Limberg

Comments, Suggestions, Articles on Total Work?

Feel free to send comments, suggestions, thoughts, and articles about total work to me at Andrew Taggart <totalwork.us@gmail.com>.

If You’d Like to Become a Patron…

Thank you so much (gassho, meaning palms pressed in gratitude) to my latest patron Daniel D.! If you feel called to support my philosophical life, you can do so here.